The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy

The next iteration of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) was approved in December 2021 after three years of tough discussions between EU governments: it will come into force in 2023, and will be effective until 2027.

Each year, it will mobilize 30% of the EU budget.

So, what is the use of this huge pile of money?

Objectives

These are all the objectives of the CAP.

- to ensure a fair income for farmers

- to strengthen competitiveness

- to improve the position of farmers in the food chain

- to act against climate change

- to protect the environment

- preserving the landscape and biodiversity

- support the renewal of generations

- to make rural areas more dynamic

- guaranteeing food quality and health

- encourage knowledge and innovation.

Did you read all of it? Well done, I didn’t. This list is not clear; because one cannot look at the CAP as a simple and coherent architectural drawing. As the CAP is the vector of all EU agricultural policy, it is a behemoth in constant evolution, to which each reform adds a head. Let’s therefore focus on the political power struggles that led to its creation and its subsequent evolution.

The CAP before 2021

Chronology

- 1957 - Treaty of Rome

- This treaty created the European Economic Community (EEC) between France, Germany, Italy and the Benelux countries, in order to create a market allowing the free movement of people, goods, services and capital. In particular, internal customs duties were abolished and replaced by external customs. It is also the announcement of future developments: the Preamble mentions that the signatories are “determined to lay the foundations of an ever closer union between the peoples of Europe”. France had demanded the addition of an article providing for the development of a “common agricultural policy”.

- 1962-1966 - Franco-German struggle 1

- For General de Gaulle, an agricultural policy that would support French farmers is a condition for integration into the European market: “An agricultural policy is due to us, in return for the serious risks we have taken, perhaps thoughtlessly or prematurely, in the industrial and commercial fields. To increase the agricultural productivity of the EEC (which did not reach, at that time, food self-sufficiency) and to ensure an income to the farmers, France supports the idea of a mechanism of guaranteed prices for the agricultural products: in the event of fall of the prices, it is a fund abundant by the States of the EEC which will ensure the minimum price. The main opponent to this measure is West Germany, which is economically much more reliant on its industry than its agriculture, and which has little interest in paying more for agricultural products than on the international market. Two major actors support the idea of the CAP: the European Commission, which naturally militates for a reinforced integration of the EEC states, but also the Netherlands, whose agricultural trade balance is good thanks to its horticultural sector. In the face of the difficulty of finding a compromise, negotiations gradually became tense. The crisis culminated in July 1965, when France began its “empty chair policy” by suspending the participation of French representatives in the EEC Council of Ministers.

- 1967 - The Kennedy Round of the GATT: free trade versus protectionism 2

- The GATT, General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, is a global treaty that aims to reduce tariffs to promote free trade. Launched in the aftermath of the war, it has been expanded and strengthened over the decades into many additional treaties. The United States have important exports of cereals and animal feed (protein cakes) to Europe, and they see the introduction of European protectionism as very bad. For the 1967 iteration, called the Kennedy Round, the priority of the United States was therefore to incorporate into the GATT an agreement on agriculture that would lower customs duties by 50% 3. France opposed this, and ended up winning the confrontation since the round ended without bringing an agricultural agreement. The negotiations on the CAP then resume in earnest.

- 1968 - The CAP comes into force

- Agricultural products enter into free circulation within the EEC. The Germans take stock of the CAP, and maintain that it is beneficial - although the benefits are much greater for France.

- 1984 - Waste and supply regulation 4

- Because of the guaranteed minimum prices, agricultural production exceeds the demand without worrying about surpluses. The result is a great waste: “butter mountains” and “wine lakes” are sold on the world market at extremely low prices. As this overproduction causes the CAP budget to explode, the EU introduces a quota system for products such as milk in 1984. Each producer can produce a certain quantity, and will be taxed if he exceeds it.

- 1992 - The GATT presses for a reformation of the CAP 3

- Faced with the demands of the USA and the “Cairns Group” during the GATT 1987-1994, called Uruguay Round, the reform carried by Ray MacSharry, European Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development, initiates a retreat from protectionism in the CAP: guaranteed minimum prices begin to fall, replaced by direct aid to farmers. This movement will continue for two decades, until the guaranteed prices disappear.

- 1999 - Rural development is added to financial aid

- Taking into account the enlargement of the EU towards the highly agricultural countries of the East, the “Agenda 2000” program aims to reduce the cost of the CAP while supporting the economic dynamism of the rural world. This reform continues to lower the minimum prices, and only partially compensates them by increasing direct aid. The budget freed up is allocated to a second pillar of the CAP: rural development. Even today, this division into two pillars - 1. Direct aids & export support, 2. rural development - still holds.

- 2003 - Introduction of social and environmental criteria

- A recurrent criticism of the CAP is that it encourages productivism and favors large farms too much. The 2003 CAP reform introduces two changes. First, the aids are decoupled from production: a single payment will be received per farm instead of a production aid. Secondly, these aids are conditional on a set of standards relating to the environment, food safety and the “welfare of animals as sentient beings”. These measures will be successively reinforced by the reforms of 2007 and 2013.

- 2013 - Green payment

- This reform makes 30% of direct aid conditional on a “green payment”, granted under three conditions: preservation of a minimum area of permanent grassland, crop diversification, and maintenance of at least 5% of arable land for areas of ecological interest: hedges, ponds.

- 2020 - Green Pact

- The Green Pact is a set of policy initiatives proposed in 2020 by the European Commission to make the EU carbon neutral by 2050. It is in this framework that the strategy “from farm to fork” was adopted, as well as an updated biodiversity strategy and a climate law in June 2021. Key agri-environmental targets by 2030 include reducing the use of chemical pesticides (-50%), antibiotics (-50%) and fertilizers (-20%); increasing the share of land devoted to organic farming to 25%; taking at least 10% of agricultural land out of production to reduce pressure on the environment; halting the loss of biodiversity on agricultural land; and reducing net GHG emissions by 55%. These ambitious targets have profound implications for the CAP.

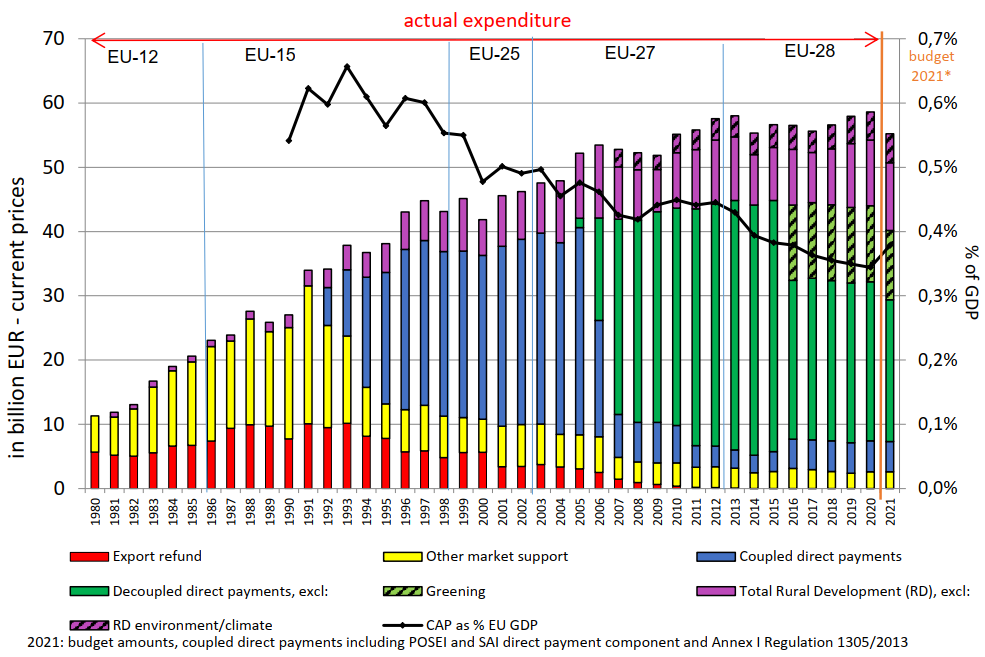

Bird’s eyeview

The graph above 5 summarizes the evolution of the CAP budget over the years. It shows the profound transformations mentioned above, sometimes implemented a few years after their promulgation: from 1992, the replacement of market measures by direct aids and the introduction of the Rural Development pillar, the decoupling of aids from 2005, the submission of certain direct aids to a green standard in 2016. The black line marks a downward trend in the CAP in relation to EU GDP, which in fact corresponds to a decrease in importance in the budget: other policies are indeed taking up more and more space in the EU budget, for example the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) which rebalances income between EU regions.

Over the years, as Europe has expanded, the net balance of each country in the CAP has changed.

We see for example that despite the large budget that France is allocated by the CAP, it is still a net deficit: indeed, the integration into the EU of new countries such as Poland and Romania, less rich and strongly agricultural, has loaded the contributions of the founding countries of the EEC.

The next CAP: 2023-2027

The Green Pact signed in 2020 is very binding for the CAP, as it requires reversing many trends 6:

- European agricultural greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have not decreased since 2010, nor have pesticide sales and nitrogen fertilizer uses.

- Organic farming areas, which currently represent 8.5% of the European Utilized Agricultural Area (UAA), would reach 12-13% in 2030 at the current rate, instead of the targeted 25%.

- Biodiversity is steadily eroding on farmland.

The new iteration of the CAP is trying to address these challenges.

Main components

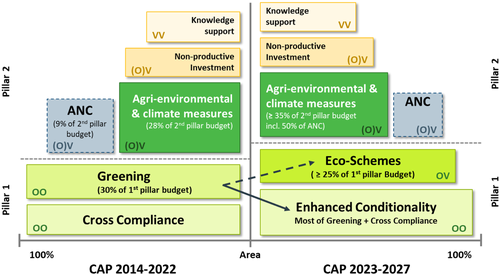

The main focus of this reform is environmental protection. It has several changes: 7

- The main novelty is in Pillar 1, with the replacement of the “Green Payments” of the previous reform: some of their constraints are taken over in the Cross Compliance part, the rest is integrated in the new system of “Eco-schemes”. The “Eco-Schemes” will be aid subject to compliance with certain standards. Another novelty: the Member States have a lot of freedom for the construction of these “Eco-schemes”; this CAP thus returns to the principle of subsidiarity of the EU at the risk of fraying the principle of a common policy.

- Reinforcement of the “Agri-Environmental & Climate Measures” (AECM) item in Pillar 2 from 30% in 2020 to 35% of payments.

- Strengthening of the Cross Compliance of direct aids:

- To combat certain abuses of employing seasonal labor under poor conditions, adding social standards related to transparency and stability of contracts, as well as safety and health standards.

- Addition of environmental standards such as maintaining 4% of non-productive surface to preserve areas of ecological interest (hedges, ponds), or mandatory rotation for farms of more than 10ha non-bio.

Criticism

As is to be expected for a policy of this magnitude, the new CAP is already attracting criticism:

- The Commission proposed the introduction of a limit on direct payments to benefit small farms, but this reform was rejected by the Council. The race to enlarge farms is likely to continue, even if the share of direct payments reserved for young farmers increases by 50% 7.

- The use of national strategic plans may result in a lesser effort by member countries, as when France’s first NSP was rejected by the Commission because it gave the same value in its “Eco-scheme” to organic crops and an easier standard called HVE 8.

- Insuffisance sur le plan de l’environnement

- Insuffisance pour préserver la biodiversité. A group of 300 European experts has formulated remarks and recommendations 9. These include the introduction of multi-annual payments in addition to the annual payments of the current eco-schemes to better address long-term issues such as biodiversity, or the necessary adoption of precise scientific indicators driven by the Commission to measure biodiversity performance.

- Finally, the fact that all the standards (social, environmental, health, animal welfare) that constrain European production still do not apply to foreign imports creates a real prejudice against EU agriculture7.

-

Ludlow, N.P. (2005) ‘The Making of the CAP: Towards a Historical Analysis of the EU’s First Major Policy’, Contemporary European History, 14(3), pp. 347–371. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/20081268.pdf ↩

-

Schoenborn, B. (2014) ‘III. Les relations économiques’, in La mésentente apprivoisée : De Gaulle et les Allemands, 1963-1969. Genève: Graduate Institute Publications (International), pp. 90–112. http://books.openedition.org/iheid/1083. ↩

-

Guyomard, H., Mahe, L.P. (1994) ‘La réforme de la PAC et les négociations du GATT : perspectives pour l’agriculture française et communautaire’. Hal-01594088. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01594088/document ↩ ↩2

-

EU consilium website - chronology of CAP https://www.consilium.europa.eu/fr/policies/cap-introduction/timeline-history/ ↩

-

Sources: CAP expenditure for past years: European Commission, DG Agriculture and Rural Development (Financial Report). GDP: Eurostat and Global Insight. ↩

-

‘Comment la PAC peut-elle aider à satisfaire les objectifs agricoles du Pacte vert pour l’Europe ?’ (2021). INRAE. https://www.inrae.fr/actualites/comment-pac-peut-elle-aider-satisfaire-objectifs-agricoles-du-pacte-vert-leurope ↩

-

Bourget, B. (2019) ‘The Common Agricultural Policy 2023-2027: change and continuity’, European Issue n°607. https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/european-issues/0607-the-common-agricultural-policy-2023-2027-change-and-continuity ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Struna, H. (2022) ‘PAC : un plan national stratégique vert pâle’. EURACTIV France. https://www.euractiv.fr/section/agriculture-alimentation/news/pac-un-plan-national-strategique-vert-pale/ ↩

-

Pe’er, G. et al. (2022) ‘How can the European Common Agricultural Policy help halt biodiversity loss? Recommendations by over 300 experts’, Conservation Letters, p. e12901. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12901 ↩