Will the Bordeaux vineyard dry up tomorrow?

In 2013, an American study led by Professor Lee Hannah made a big splash: the average temperature in the Mediterranean climate increasingly exceeding the needs of the vine, large areas would become unfit for viticulture in the next forty years, especially on the Mediterranean rim. So, are our vineyards doomed?

Heat and vines

In order to better understand the stakes of global warming for viticulture, let’s first look at the production cycle of a vintage.

The vine cycle

It begins like a birth, with tears: after the first warm days of spring, the vine comes out of its winter sleep, and its sap flows like tears through the wounds left by pruning. Then the buds come out of their cotton buds to start growing. It is after this budding that the frost is dangerous, because the plant lowers its defenses against the cold. At the end of May, the flowers bloom, then slowly swell into seeds. The fruit ripens and, depending on the variety, is loaded with sugar, tannins and, in the case of black grapes, anthocyanins that give them color. When the grapes are ripe, they are harvested and the vinification begins in the cellar. If each phase takes place under mild skies, and if the vine can grow, guided by the tireless work of the winegrowers, without being ravaged by hail, frost, mildew, or by the bumper of a drunk driver leaving at great speed from the Châteaux road, only then can the wine be good.

The importance of heat

Throughout this cycle, the ideal weather conditions change dramatically. The winter must be cold for the vine to build up its reserves; on the contrary, during the ripening period, the ideal weather is that “baking sun” that the soul of wine sang about in the words of Baudelaire. This last condition is the most important: for example, without heat, the Cabernet-Sauvignon keeps heavy aromas of green bell pepper which unbalance its bouquet. The art of winemaking cannot be summed up in temperature alone, but the study shows that the wines of the last century were on average better after hot summers. An American economist, Orley Ashenfelter, put this relationship into an equation: he was one of the first to predict that the very hot and dry summer of 1982 would produce an excellent year. His compatriot, the young critic Robert Parker, also made this audacious announcement - and he gained worldwide renown for it, as 1982 proved them right, gradually revealing itself as one of the great vintages of the century.

Too hot?

However, when temperatures are too high, good wine cannot be made. In Bordeaux, the summer of 2003 is an illustration of this: the intense heat wave blocked the ripening of the grape varieties - Merlot in particular - and produced overripe tannins. It was with this in mind that the 2013 study was published, which predicted a decline in traditional wine regions.

The adaptation of vineyards

Are we seeing a massive migration of European vineyards to the North? See for yourself.

Evolution of the surface of vineyards between 2000 and 2018. In black the areas that remained vineyards, in green the new vineyard areas, in red the areas that were changed to another use. If there was a general migration of vineyards to colder latitudes, we should have a green dominance in the North and red in the South.

It appears that there is no clear trend between 2000 and 2018. Lee Hannah’s team went too far in their conclusions, because they took climate as the only force at work. After the publication of this study, an energetic response was quickly published, led by Professor Van Leeuwen, who criticized the team for having omitted a major factor: the work of the vineyard.

“Wine is the son of the sun and the earth, but it has had work as its midwife.” Paul Claudel

Winegrowers have not waited for anyone to adapt their methods to climate change: viticulture around the world is full of new ideas, and the great Bordeaux vineyards are veritable open-air laboratories. Many practices are being tested: for example, letting grass grow in the rows increases the albedo of the soil - the radiation reflected back to the sky instead of being transformed into heat. The Laccave science project is producing a census of these trial adaptations.

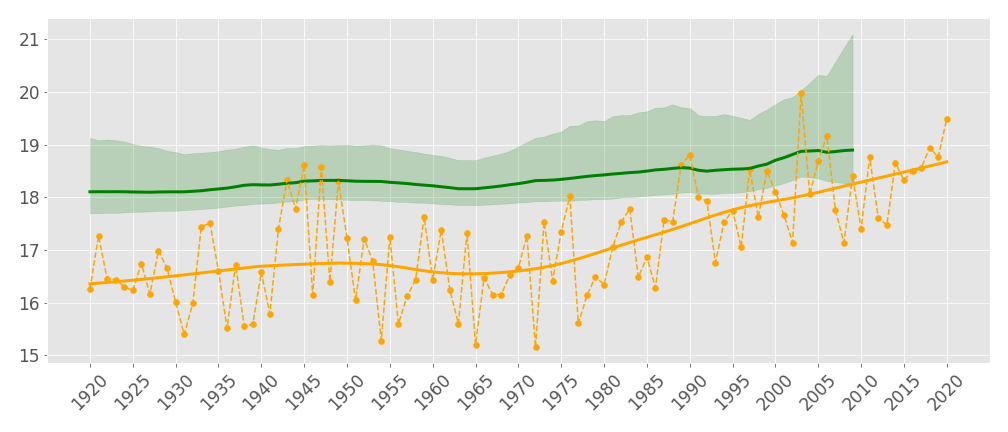

Pablo Almaraz, researcher at the University of Cadiz, has shown the tangible impact of this adaptation. He studied the relationship between the quality of Bordeaux wine, reported for over a century by a Bordeaux broker, and the average temperature from April to September. He thus managed to obtain an estimate of the optimal temperature: we then obtain the graph below, where we see that, since 1970, the increase in temperature is preceded by a progressive increase in the optimal temperature.

The road ahead

So, is the Bordeaux vineyard safe? It seems that the work in the vineyard - and no doubt also the winemaking and maturing - has been able to adapt with a tangible effect. But this is probably only time saved, before we reach the physical limits of the vineyard - let’s remember that the median scenario given by the latest IPCC report leads very likely to a global temperature increase of more than 2°C by the end of the century, in particular an increase of 4°C in Europe. What will be the impact on viticulture? Temperatures above 40°C can dry out the grapes and cause apoplexy on the vines. Australian and Californian vineyards are already accustomed to this damage, and France experienced it painfully in June 2019, when a record 45°C was recorded in Marsillac, drying out a third of the Hérault harvest on the ground.

The French viticulture world has wholly measured the threats that loom ahead : a partnership including the great state research organism INRAE has built a national strategy of the winemaking indsutry against climate change. Among the four scenarios envisaged for 2050, a “nomadic” scenario, which would involve relocating vineyards, thus calling into question our terroirs. To avoid this scenario, the industry will have to rely on a number of pillars, the last of which goes back to the root of the problem: since global warming is a societal problem, and since the wine industry will be asking the government for help in the difficulties to come, it will have to be exemplary in mitigating this warming.